- Here are some historical examples. The 1980s S&L crisis, Black Monday in 1987, The 2000 dot-com crash, & 08 Financial...

- A study published in May of rate increases for 17 developed countries over 150 years concluded that “monetary policy rate hikes that were preceded by a series of cuts (or a long period of low rates) materially increase crisis risk.”

- The “U-shaped monetary rate path,” as a senior researcher from the Bank of Spain and three co-authors called it, “increases banking crisis risk, via credit and asset price cycles.”

- The yield on 10-year Treasury notes topped 5% this week for the first time since 2007.

Higher yields have often exposed weak players that took big risks

Interest rates have soared. Can financial blowups be far behind? Maybe, but often it isn’t that simple.

The yield on 10-year Treasury notes topped 5% this week for the first time since 2007. While not high by historical standards, it is a big move from less than 1%, where it was for most of 2020.

“Five percent is more or less the average of investment-grade rates since the time of Alexander Hamilton,” said James Grant, founder, and editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer. “The problem is the structures that 10 years of ultra-easy money brought about. People blame it on the normalization of rates. The previous bout of abnormal rates is the problem.”

We have already had two sets of blowups since interest rates started rising in 2022. In the U.S., the surge triggered regional-bank failures earlier this year. In the U.K., leveraged pension funds were slammed by higher rates a year ago. In both cases, governments intervened to keep the problems from spreading.

Historically, big lurches in monetary policy increase the chances of something going haywire in financial markets. A study published in May of rate increases for 17 developed countries over 150 years concluded that “monetary policy rate hikes that were preceded by a series of cuts (or a long period of low rates) materially increase crisis risk.” The “U-shaped monetary rate path,” as a senior researcher from the Bank of Spain and three co-authors called it, “increases banking crisis risk, via credit and asset price cycles.”

Sometimes the cause-and-effect linkages between rising rates and financial blowups are clear-cut. Other times they are more muddled. Credit losses, liquidity crunches, and high leverage often play crucial roles, with no way to cleanly isolate the effects of different factors.

Here are some historical examples.

The 1980s S&L crisis

The Federal Reserve’s interest-rate hikes to combat inflation during the late 1970s and early 1980s rendered much of the U.S. savings-and-loan industry insolvent. The federal government set the rates that thrifts were allowed to pay on deposits, and many customers pulled their money to seek higher returns elsewhere.

At the same time, S&Ls mainly made long-term, fixed-rate mortgages. The market values of those assets plunged as rates soared. (A similar scenario happened at

and Silicon Valley Bank, which collapsed this year.) Regulators let zombie thrifts persist for years, and their financial condition got worse. By the late 1980s, more than 1,000 thrifts failed, and Congress approved a taxpayer bailout.

Continental Illinois National Bank & Trust

Continental Illinois National Bank & Trust was the seventh-largest U.S. bank in May 1984 when it suffered a global run on its deposits. That coincided with the 10-year Treasury yield breaking 13%, up from just over 10% a year earlier. The bank had grown rapidly, making risky loans at below-market rates even while interest rates were soaring. A Chicago competitor in 1981 told The Wall Street Journal, “Even with a 20% prime they were doing 16% fixed-rate loans. I don’t know how they do it.”

Banking regulators ultimately provided several billion dollars of assistance and guaranteed all depositors and creditors, leading Continental Illinois to be dubbed the original “too big to fail” bank.

Black Monday

Postmortems about the Oct. 19, 1987, stock-market crash, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average slid 22.6%, often point to program-trading strategies—with names like portfolio insurance and index arbitrage—that snowballed into giant losses. Margin calls ensued, and the computerized trading systems of that era couldn’t handle the transaction volumes.

But interest rates and currency markets were crucial drivers. The dollar had been weakening against the West German mark, while the 30-year Treasury yield rocketed past 10% from 7.5% in March. When rates go higher, stocks often decline because companies’ future earnings are worth less. Stocks kept going up anyway that summer, setting the stage for a swift fall.

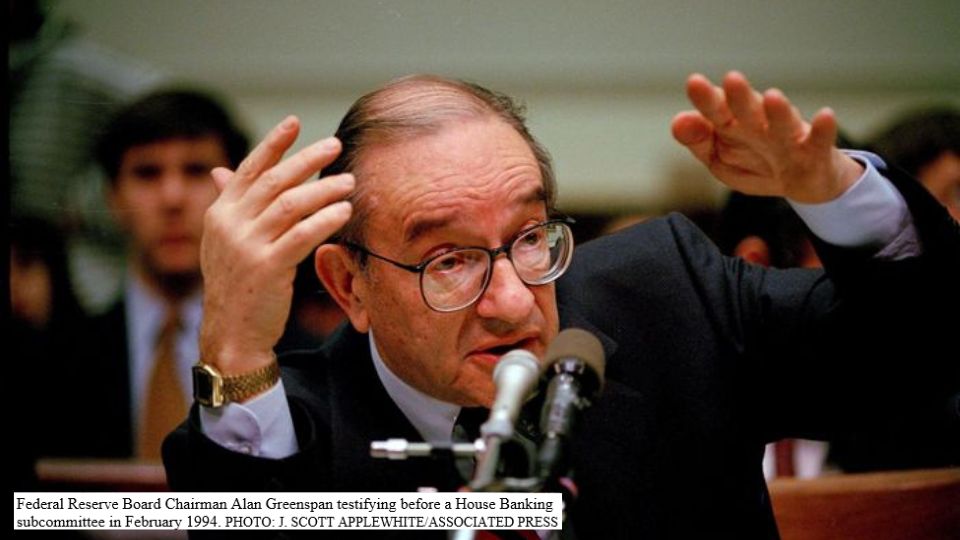

1994

The Fed surprised the market by doubling interest rates to 6% in 12 months. The increases tanked bond portfolios, along with Mexico’s economy, and exposed a scandal over phony trading profits that sank the Wall Street brokerage firm Kidder Peabody.

The hikes included a 0.75-point increase in November. The next month, Orange County, Calif., filed for bankruptcy, after a series of disastrous, wrong-way bets on rates. The county treasurer resigned and later pleaded guilty to fraud.

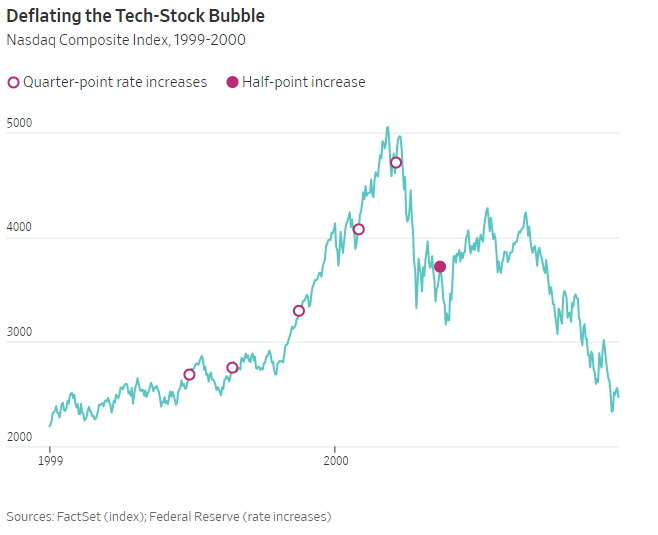

The 2000 dot-com crash

Speculators taking fliers on the next cash-torching, dot-com darling didn’t care about investment fundamentals. The deflating of the internet-stock bubble had many culprits.

But it is true that the Fed did raise rates six times from June 1999 to May 2000. The last of those was by a half-point to 6.5%. By then, the bubble already had been pricked. Rates fell to 1% by 2003, setting the stage for nearly two decades of mostly low rates.

The 2007-09 recession

Here, the Fed is more often blamed for leaving rates too low for too long than for raising them too high. It increased rates 17 times from June 2004 to June 2006, in each instance by a quarter-point. Signs of a housing downturn were surfacing when it stopped. By 2007, the start of the financial crisis was under way, and the Fed resumed rate cuts again later that year.

For millions of Americans, the impact of higher interest rates hit home directly, because they had taken on adjustable-rate mortgages that reset higher after their rock-bottom introductory rates expired. Often the customers could afford to pay only the initial teaser rates, while the lenders didn’t care because they quickly sold off the loans to investors in bundles backing complex mortgage bonds.

The ensuing credit losses might have been more about lax underwriting standards than rising rates. But the higher rates when the loans reset contributed to record numbers of foreclosures, nonetheless.

Story by Jonathan Weil - Redacted bullet points by Jody Davis https://www.wsj.com/finance/with-interest-rates-up-get-ready-for-financial-drama-6c055fb5